In the relentless pursuit of agricultural efficiency, the land beneath our feet has quietly borne the brunt of our ambitions. As we treat the earth as a perpetual cropland, we’ve come to rely heavily on mineral fertilizers, especially those rich in ammonia, to boost yields and generate short-term profits.

This approach, however, leaves out a crucial consideration: the health and sustainability of the soil itself. In the pursuit of quick profits, we risk the future of the very foundation on which our agriculture depends.

The Shortcomings of Current Practices

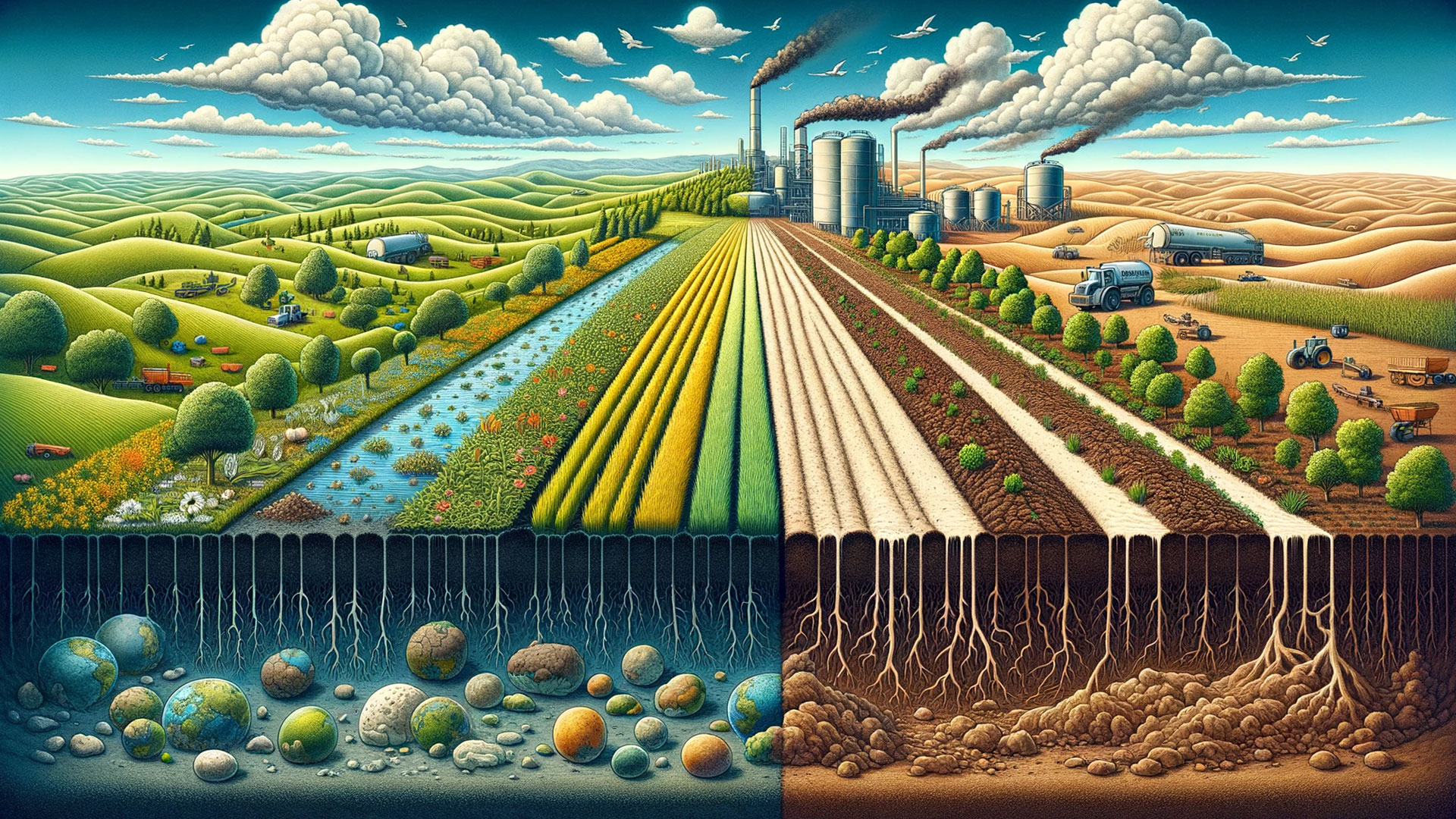

The modern agricultural paradigm often prioritizes quick returns, viewing the land as an inert medium rather than a living ecosystem. This perspective has led to an overdependence on synthetic, mineral fertilizers that, while effective in the short term, can degrade soil structure, reduce biodiversity, and lead to nutrient runoff polluting waterways. The irony is palpable: in our quest to maximize productivity, we are depleting the soil of its natural fertility, setting the stage for diminished returns and environmental degradation.

The Price of Convenience

Mineral fertilizers, with their concentrated and readily available nutrients, offer the alluring promise of simplicity and efficiency. They act like an ammonia needle, injecting the soil with a quick fix of nutrients that stimulate growth but do little to maintain long-term soil health. This approach treats the symptoms of soil depletion without addressing the underlying causes, such as loss of organic matter and disruption of natural nutrient cycles. The result is a vicious cycle of dependency where more and more fertilizer is needed to achieve the same yield, further exacerbating soil degradation.

Organic Alternative

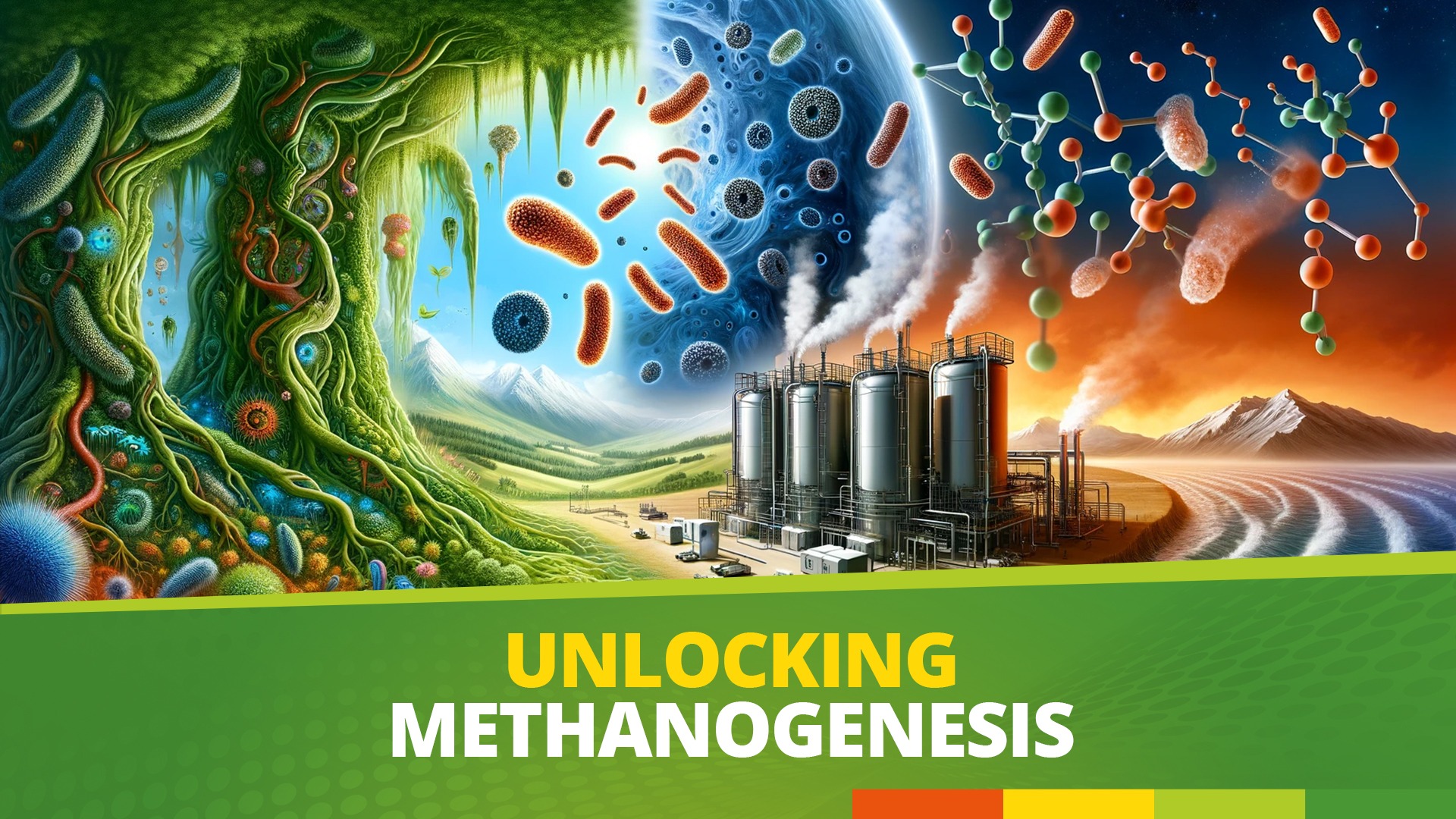

The solution to breaking this cycle may lie in what we’ve long considered waste. The depleted soils of many countries today are crying out for restoration, and the key may lie in using yesterday’s waste – by fermenting it in biogas plants. Digestate, the nutrient-rich by-product of anaerobic digestion, offers a sustainable alternative to mineral fertilizers. Not only does it provide a broad spectrum of nutrients in a more balanced and plant-available form, it also incorporates organic matter that helps rebuild soil structure, improve water retention and promote microbial diversity.

Embracing a circular approach

Sooner rather than later, we will have no choice but to return to the basics of soil health. Using digestate and composts to rejuvenate our soils is a step toward a more circular, sustainable form of agriculture. By recycling organic waste into a valuable soil additives, we can reduce our reliance on synthetic fertilizers, mitigate environmental impacts, and support the long-term productivity of our agricultural systems. This approach not only meets the immediate needs of crops, but also ensures soil resilience and fertility for future generations.

What lies ahead

Overdependence on mineral fertilizers reflects a broader issue in our approach to agriculture and environmental stewardship. If we continue to treat land as a mere production space, ignoring the intricacies of soil health and nutrient cycles, we will approach a point of diminishing returns. But by recognizing the potential in materials we’ve traditionally viewed as waste, we can shift to a more sustainable and regenerative model.

The choice is clear: continue down the path of dependency and degradation, or turn to solutions that restore and revitalize. For the sake of our soils, our environment, and our future, let’s choose wisely.

| Factor | Mineral Fertilizers | Organic Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Short-term Benefit | Immediate yield increase | Gradual improvement in yields, sustainable in the long term |

| Long-term Soil Health | Degradation of soil structure, reduction in biodiversity | Improved soil structure, increased biodiversity |

| Sustainability | Increased dependency, environmental pollution | Enhanced soil fertility, reduced pollution |

| Biodiversity | Reduced due to chemical runoff and habitat destruction | Promoted through natural nutrient cycles and organic matter |

| Dependency Cycle | Creates a dependency for repeated applications | Breaks the cycle by naturally enhancing soil fertility |

| Cost-effectiveness | Initially lower costs, but increases due to dependency | Higher initial investment, but more cost-effective long term |

| Environmental Impact | Pollution and contribution to climate change | Reduced carbon footprint, supports climate change mitigation |

This table contrasts the immediate benefits and long-term consequences of using mineral fertilizers with the holistic and sustainable advantages of organic alternatives in agriculture.